The Ogg Backlog

Like an arsonist seeking credit for dousing flames on the house she lit on fire, Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg has made the rounds on local media—everywhere from the Houston Chronicle to Houston Style Magazine—over the past few weeks desperately seeking credit for a modest reduction in the notorious backlog of criminal cases that she herself made worse.

The backlog refers to the number of cases that are awaiting trial in Harris County. A big backlog of lingering cases is bad for crime victims, who deserve timely justice—especially since evidence, including human memory, often degrades as time passes. It’s also bad for the accused, including people who are innocent, who are locked in overcrowded jails waiting months or years for trial.

According to the DA’s own numbers, the backlog reached a high of 145,000 cases. At that point, a typical case could take 432 days—well over a year—to reach trial. It’s now down to about 115,000 cases. In other words, a reduced, but still massive, backlog.

But here’s the thing: It’s Ogg’s policies and management practices that have fueled and sustained this backlog, delaying justice for victims and making the county less safe.

A comprehensive independent report from the research firm, PFM Consulting Group, strongly suggests that Ogg’s leadership and management style contributed to the backlog. For example, the report noted that critical departments within the District Attorney’s Office were staffed with “inexperienced prosecutors [who] lack the knowledge and insight that comes from prosecuting cases.”

The report also noted that Ogg’s “inherently inefficient” case management structure resulted in “frequent reassignment”—read: more delays—and resulted in a situation where prosecutors “do not feel responsible for working up the case, tracking down discovery, and ensuring that it moves forward.” The report even recommended that Ogg provide rudimentary training to prosecutors on “time management” and “conducting effective meetings.”

Sadly, senior leadership in Ogg’s office—specifically, the chiefs who run the various divisions—reported skepticism that these training recommendations would matter much, given that under Ogg’s leadership so many “attorneys burn out quickly and resign.” The findings from the PFM report are echoed in reviews that Ogg’s staff have left on employment websites such as GlassDoor: Under Kim Ogg’s leadership, the Harris County District Attorney’s Office garnered just 2.6 stars. Just 7% of employees approve of the District Attorney’s leadership.

In sum, low staff morale and “inherently inefficient” process leads to high turnover, driving a vicious cycle of more delays and new, more inexperienced prosecutors, which then leads to even more delayed handling than if an experienced senior prosecutor was still on the case.

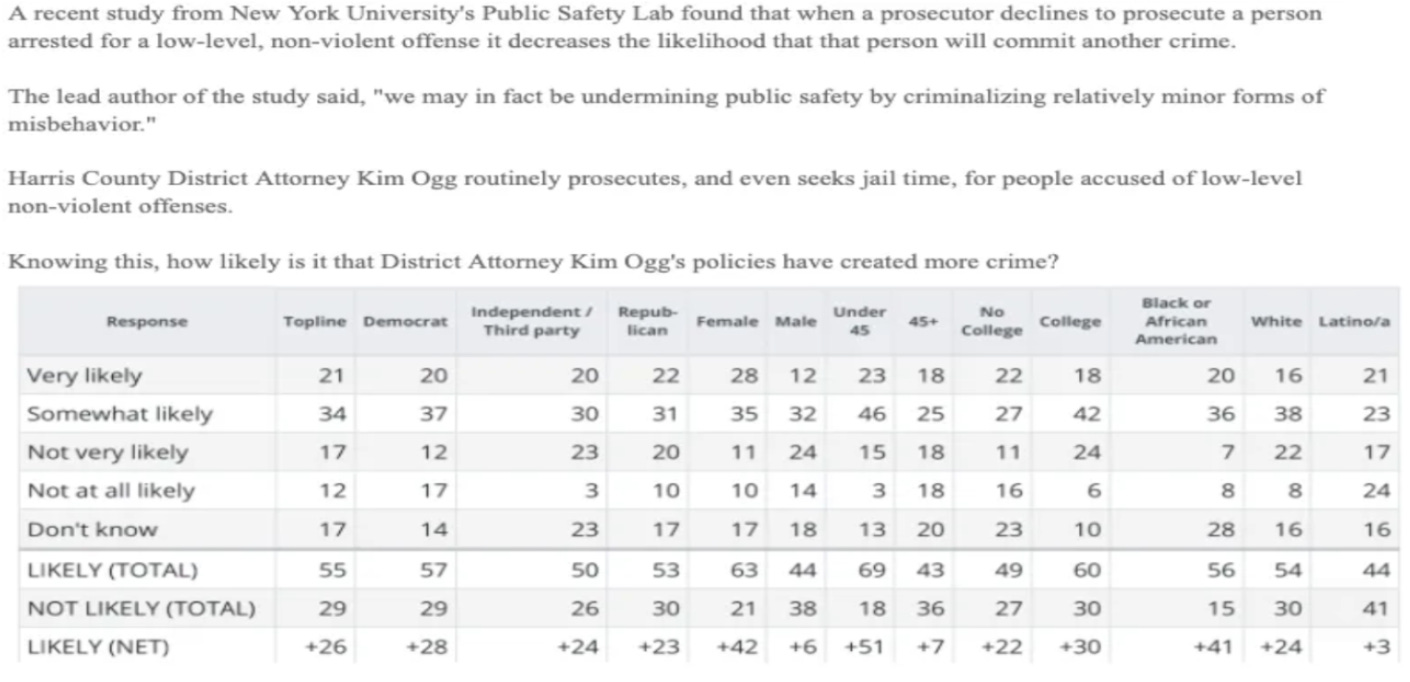

In addition to these management-based concerns, Ogg’s stubborn refusal to triage cases in order to ensure adequate attention for the most serious and violent offenses crowded court dockets at a time when law enforcement leaders and prosecutors across the country were putting their heads together to thin courthouse dockets. Instead, Ogg continued to prosecute low level, non-violent offenses—even in situations where strong empirical research suggests that formal prosecution can increase the risk of future offending by, for example, disrupting employment and relationship stability. Refusing to triage needless—even unwise—prosecutions resulted in a larger backlog and made it more difficult for prosecutors to focus their time on cases like drunk driving and murder. Unsurprisingly, then, when these cases finally arrived at trial after massive delays, Ogg’s office frequently lost them.

You don’t need to be inside the courthouse to understand how much Ogg’s practices inhibited the reduction of the backlog and harmed public safety. Indeed, a poll of Harris County likely voters found that 55% of respondents—including 57% of Democrats and 53% of Republicans—believe that “District Attorney Kim Ogg’s policies have created more crime.”

None of this is to suggest that the modest reduction in the backlog isn’t worth celebrating. It is, and many hardworking prosecutors inside the Harris County District Attorney’s Office deserve credit for any reduction, as they’ve had to work nights and weekends to make that progress. The Harris County Commissioner’s Court deserves credit, too, for rerouting resources to courts and the District Attorney’s Office to help address the enormous backlog.

What would most help the hard working women and men inside the District Attorney’s Office—and certainly help crime victims and family members—is for Ogg to focus less on a mirage victory lap over the modest backlog reduction and instead implement the meaningful management and case processing decisions that would provide deep cuts to the backlog while devoting adequate attention to winning serious cases like DWI and murder at trial.