Ogg’s Office Botched Another Murder Case

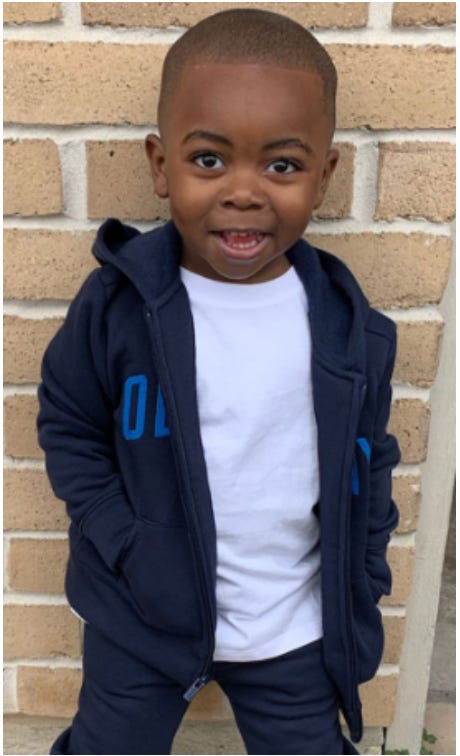

The same man now faces trial for gunning down a 2-year-old boy.

Last week, in a trial defined by prosecutorial sloppiness, the Harris County District Attorney was slapped with yet another not guilty verdict in a murder case.

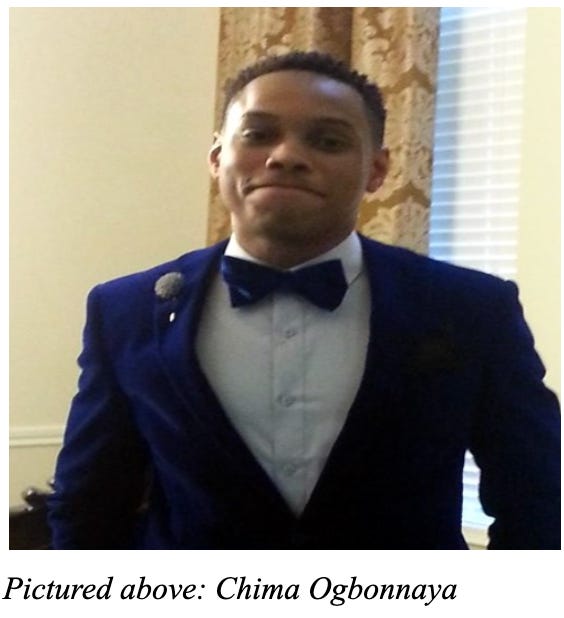

In March of 2019, 22-year-old Chima Ogbonnaya was shot to death in the parking lot of an office building. Prosecutors and police said it was an attempted robbery.

According to the Houston Chronicle, multiple witnesses identified Cecil Lakey as the shooter, saying he “was a passenger in a maroon Chevrolet Impala” and “shot at Ogbonnaya . . . as he drove past”.

It’s possible that the defendant is actually innocent despite the witnesses and other solid evidence suggesting his guilt. Though it’s worth noting that he hasn’t conducted himself in jail like a man who is falsely accused. His disciplinary record while locked up would make even the most hardened of prisoners blush: assaulting at least seven different inmates, trying to start a fire, threatening a prison guard, and trafficking banned items. Indeed, Lakey has never exactly been a good candidate for a Nobel Peace Prize: He’s faced charges for burglary of a vehicle, unlawfully carrying a weapon, and evading arrest, among other lowlights. And he’s also currently in the Harris County jail awaiting trial on a separate murder charge for gunning down a 2-year-old.

But the real point is that it is impossible to know if a guilty person is off the hook for murder because Ogg’s office didn’t—or couldn’t—bring the level of preparedness and professionalism that every murder case deserves.

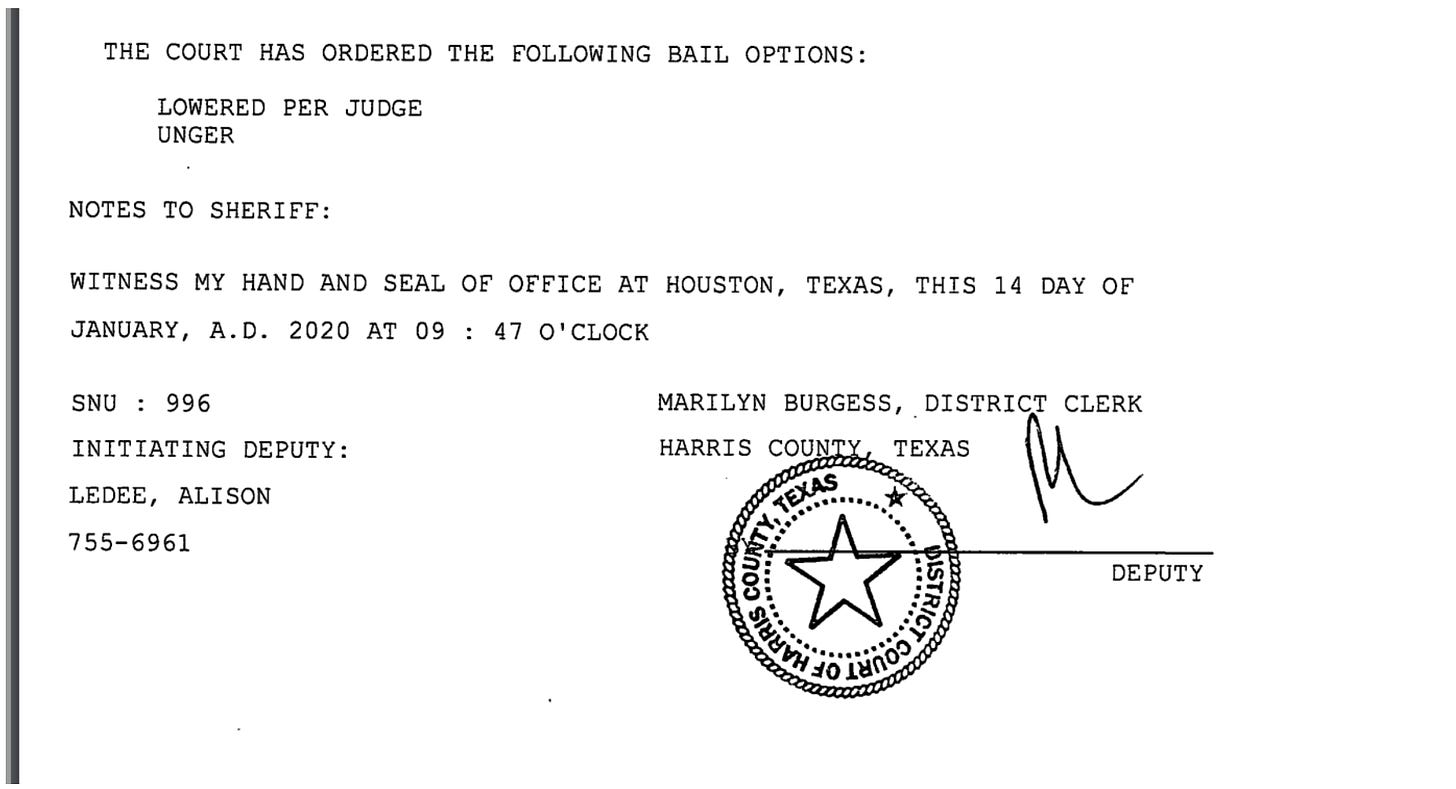

Hints that the prosecution wasn’t taking the murder of Chima Ogbonnaya seriously enough first appeared when the trial judge had to reduce the defendant’s bail by a quarter million dollars because the state wasn’t ready for trial. Since it had been more than three months, Texas law required the court to reduce bail to an amount the defendant could afford to pay.

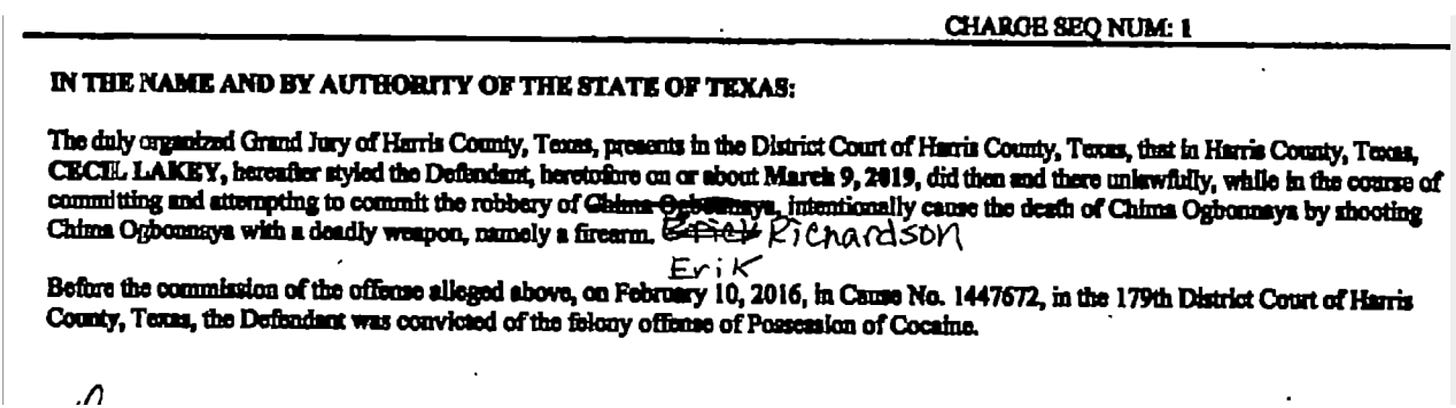

Then, on two occasions, Ogg’s office had to beg the judge to allow them to amend the indictment against the defendant. First, the Harris County District Attorney Office listed the wrong person as the alleged robbery victim. Months later, prosecutors had to head back into court, tail between their legs, to ask the judge to amend the indictment once again—this time to “correct the spelling of the complaining witness’ name.”

But the real messiness happened at the most inopportune time—during the actual trial. After witnesses finished testifying for the day, prosecutors informed the court of a discrepancy between the notes that a prosecutor wrote summarizing a statement from a key witness and what the witness said he remembered as he prepared to testify at trial.

Specifically, though the prosecutor “had written down that [the witness] heard [the] [d]defendant say ‘Damn I shot’, ‘it went wrong so I had to shoot’, and that he actually saw the gun in [the defendant’s] hand immediately after the shooting,” the witness told a different prosecutor that he “cannot say that he now independently remembers things happening at this time.”

Call it sloppy note taking, or chalk it up to inadequate witness interviewing and preparation, or blame it on the fact that it took prosecutors nearly four years after the murder to take the case to trial … it doesn’t matter. Each of these explanations point to the same conclusion: when prosecutors stumble, accused murderers go free.

Not coincidentally, Kim Ogg herself got involved in the case, filing a motion that reflects the tried and true two-step process for a prosecutor looking to clean up a major mess that they’ve created with a key prosecution witness: first, ask the judge to force the witness to testify; and, second, offer that witness immunity from prosecution. That’s a huge incentive for the witness to start to—in the parlance of one of the trial prosecutors—“independently remember[] things happening …”

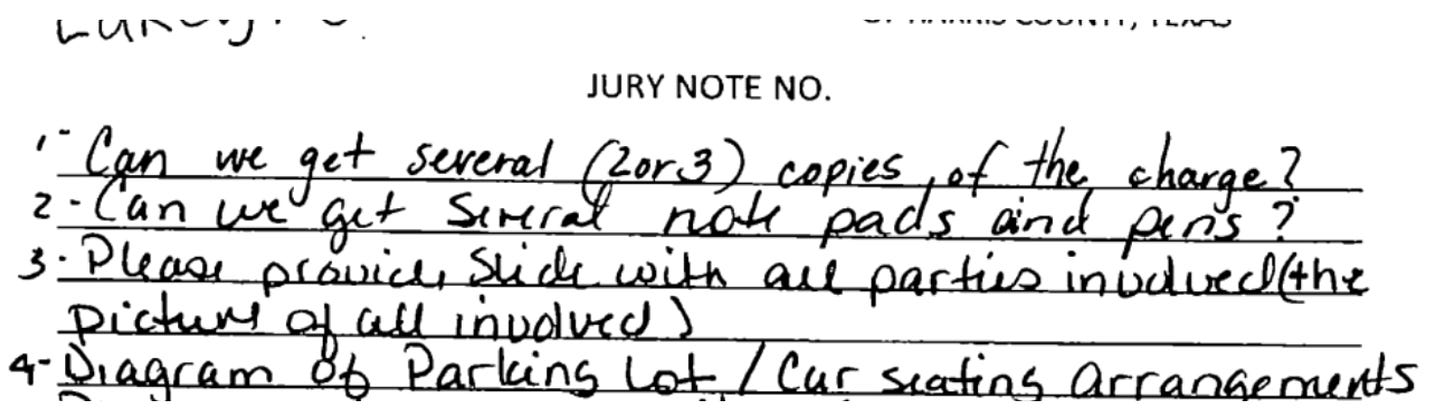

But Ogg couldn’t save the day. In the end, attention to detail wins murder trials. And as reflected in a note from the jury during their deliberations, the prosecution didn’t exactly dot their Is and cross their Ts.. Even after hearing the prosecution’s entire case, jurors still didn’t have a clear sense of basic information such as “all parties involved” in the shooting altercation, where people were seated in the two cars involved in the shooting, or even a sense of the layout of the parking lot where the altercation began.

Prosecutors couldn’t even effectively explain the basics of what happened and who was responsible. Unsurprisingly, then, the jury returned a verdict of “not guilty.”

Today, the defendant is still locked up awaiting trial for the murder of a 2-year-old boy. It has been nearly four years since the toddler was gunned down. There’s still no trial date. Why?

You know why. Once again, Ogg’s office isn’t prepared.

Indeed, the trial judge had to delay the murder trial for a second time last month because Ogg’s office had not yet sifted through and disclosed cell phone records that the defendant has the right to review before trial. As the defense lawyer told the judge, the cell phone records “are in the possession of the State, but have yet to be downloaded or vetted for evidentiary information.”

Is it too much to expect that Ogg’s office would bother to sift through key evidence in the nearly four years between the killing of a baby boy and the trial date for bringing the person who allegedly shot him to justice? And, given that Ogg seems to not have made adjustments to the level of professionalism and diligence that she demands from prosecutors trying murder cases, do we dare expect anything other than a not guilty verdict in this case, too?