Crime Stoppers Caught Seeking Special Treatment For Board Member’s Babysitter

Just past noon on a Wednesday this past April, a Houston police officer clocked a 26-year-old woman speeding down a highway service road just a few minutes from Jonathan Zadok’s home in upscale Bellaire. Though the area is among the most affluent in the country, the driver of the speeding car later filed a financial indigency application in criminal court reporting that she made only $800 per month working as a full-time au pair for the wealthy Mr. Zadok and his family.

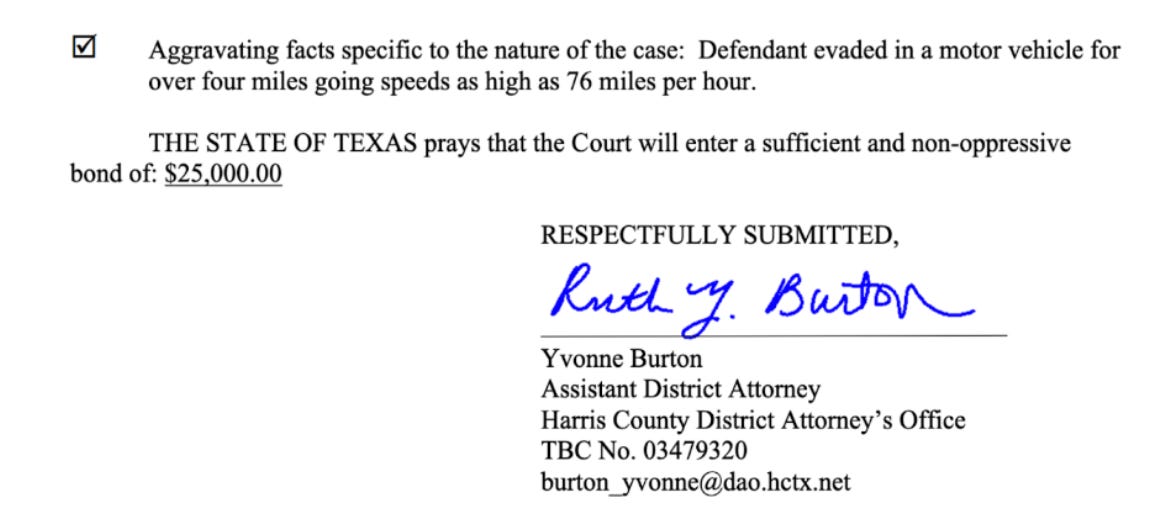

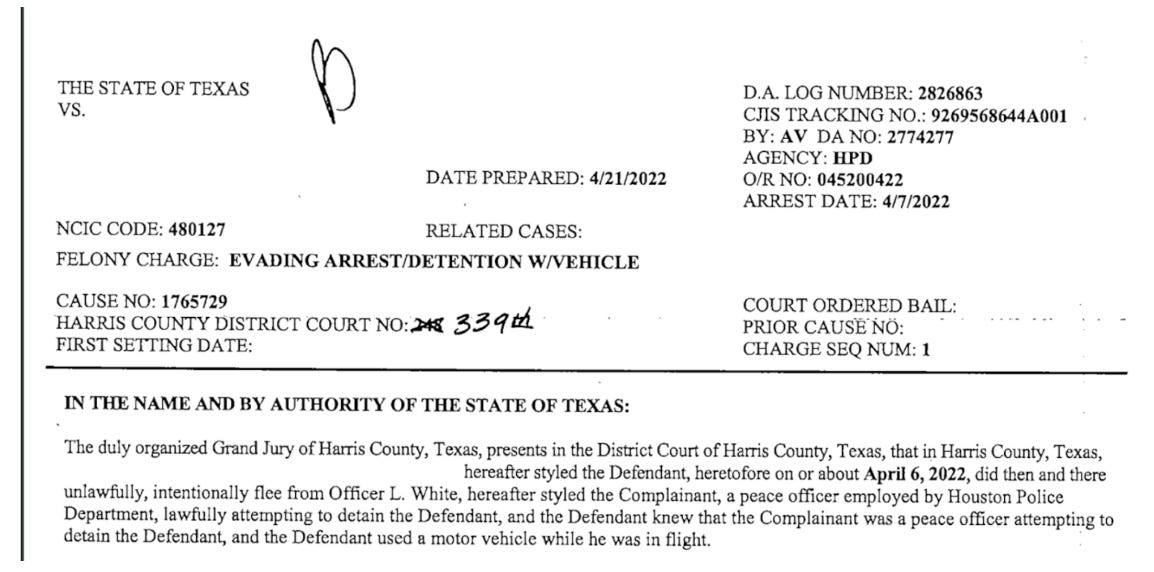

None of this would matter much to anyone except that instead of stopping in the face of flashing lights and a blaring siren, the woman just … kept … driving. She allegedly led the police officer on a four mile chase that at times reached speeds of 76 miles, more than doubling the posted speed limit on stretches of the service road. It’s no white Bronco, but it’s probably the most exciting thing that’s ever happened for the high society circles that Zadok—owner of Zadok’s jewelers, and jeweler to Houston’s wealthy and powerful—travels in. Ultimately, the officer apprehended the woman and charged her with felony evasion of the police.

Evading the police is a serious charge. In Harris County, it is not unusual for a person to be sentenced to a multi-year prison term after a felony evasion conviction. That’s why the assistant district attorney assigned to the au pair’s case asked the judge to hold the woman in jail unless she could pay a $25,000 bond.

But when it comes to facing consequences for high speed chases in Harris County, it’s not how fast you go, but who you know. Or, at least that’s what Zadok, a board member of Crime Stoppers of Houston, and his friend, Rania Mankarious, the organization’s embattled CEO, were counting on. On at least two different occasions, Mankarious reached out to Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg to ask her to personally review the babysitter’s case.

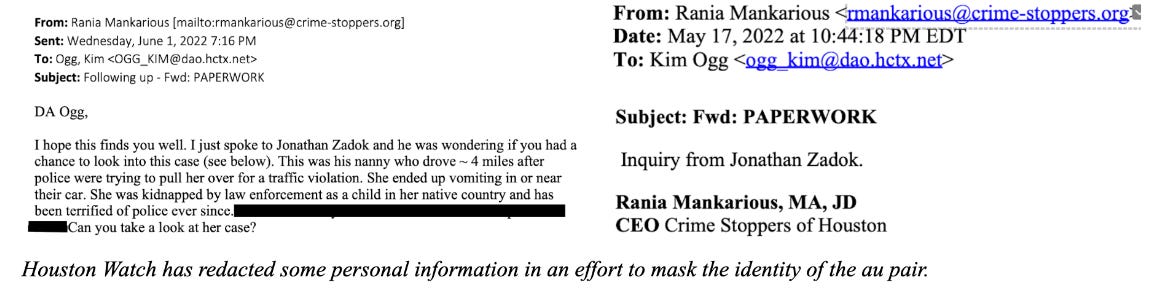

“Inquiry from Jonathan Zadok.”

That’s the cryptic text contained in a May 17th, 2022 email from Ms. Mankarious to District Attorney Ogg. The email contains a forwarded email from Zadok to Mankarious with the text “information on the case for our Au pair to pass along,” the cause number, and a reminder that “Ogg can access” the “full package of explanations” into his nanny’s behavior through the online court docket. Mankarious fired off this email to Ogg just three weeks after a grand jury returned an indictment against the au pair on felony evading the police charges.

Two weeks later, Mankarious again emailed Ogg about the case—“I hope this finds you well. I just spoke to Jonathan Zadok and he was wondering if you had a chance to look into this case,” Mankarious wrote on June 1, 2022. “This was his nanny who drove ~ 4 miles after police were trying to pull her over for a traffic violation.”

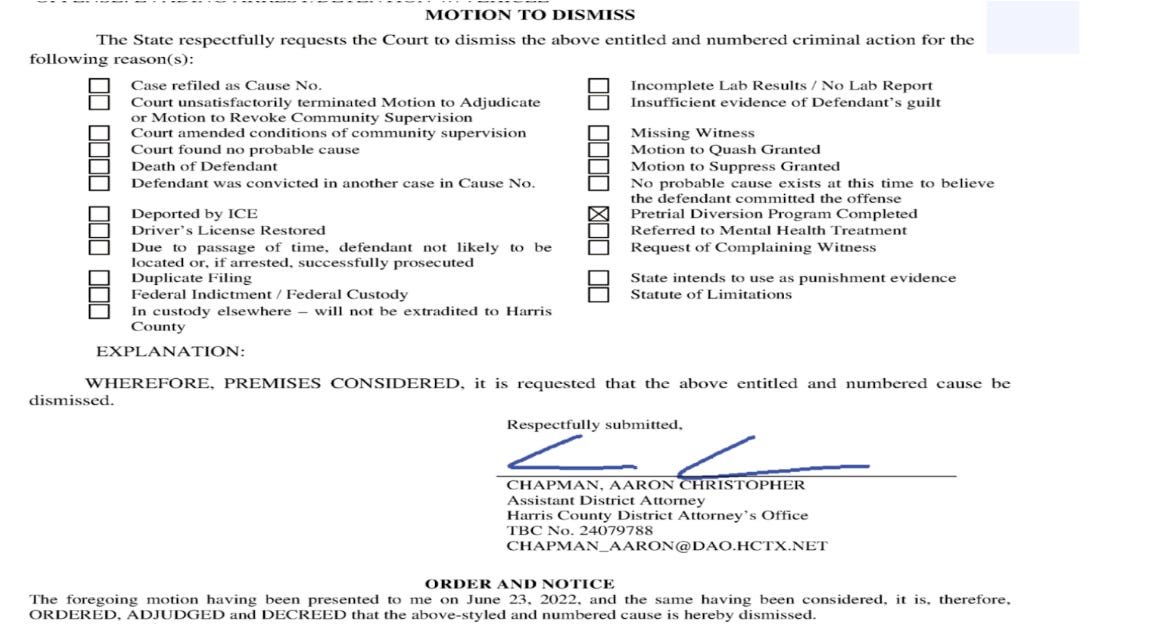

Just three weeks after Ms. Mankarious’s follow-up email to D.A. Ogg, the Harris County District Attorney’s Office filed a motion to dismiss the charges in the felony case, citing the fact that the au pair had “completed” a “pretrial diversion program.”

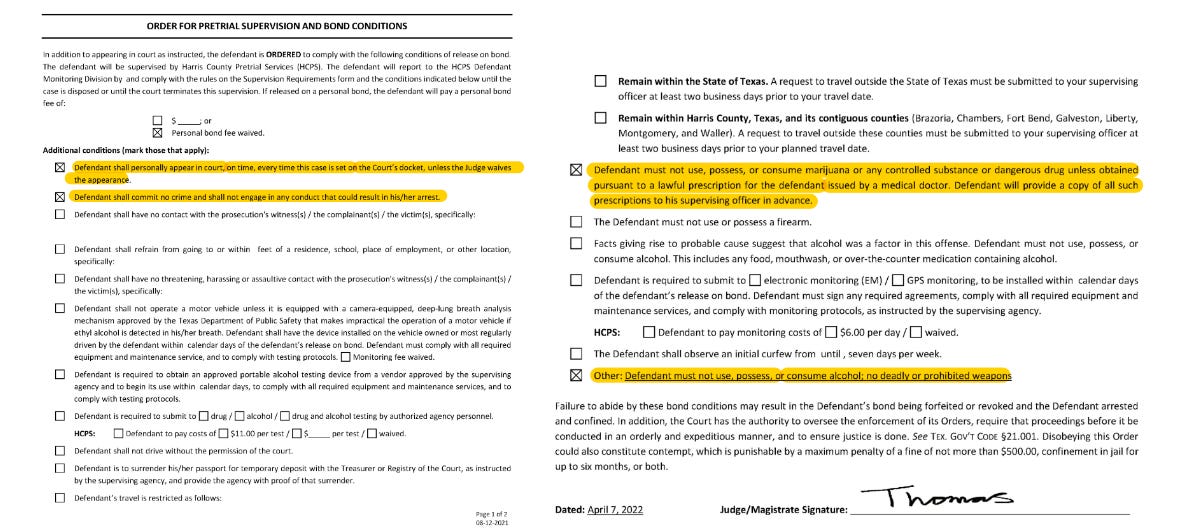

There is no online record containing any specifics on either the substance or length of this “diversion program.” Houston Watch contacted the county clerk’s office, and a representative confirmed that the conditions of the au pair’s release on bail are the only conditions in the record. In other words, it appears that in this case “pre-trial diversion” is a euphemism for “so far has not violated her original bail agreement.”

What were the conditions of that agreement? You can read them below:

The unusual outcome in this case raises three different timing-related red flags:

The short time period between arrest and the resolution of the case. There is a notorious criminal case backlog in Harris County. As Robert Arnold, an investigative reporter for KPRC reported earlier this year, the average time it takes to dispose of a criminal case in Harris County is well over one year—492 days. By contrast, this felony evading arrest case lasted two months and seventeen days; or, over a year less than the typical case.

The short length of the “pretrial diversion program.” The au pair’s case traveled from indictment to completion of a pretrial diversion program in the span of two months—even though some people go to state prison when convicted for evading the police. Murray Newman, a respected Houston criminal defense lawyer, told Houston Watch that felony diversion programs are not typically completed within a few months of arrest. “Felony pretrial diversions are normally a year, if not two,” Newman said.

The short timeline between Rania Mankarious’s follow-up email to Kim Ogg and the resolution of the case just three weeks later. It could be a coincidence that the case reached a resolution so quickly after the email intervention from Mankarious, but given both the criminal court backlog and the head-scratching length of the pretrial diversion program at issue in the case, the timing of the Mankarious–Ogg exchange just doesn't smell right.

The important point here is not what the outcome in the au pair case should have been. For starters, as a young child, this woman endured a traumatic incident with police officers in her home country that has left her afraid of police as an adult. That’s a relevant mitigating factor that helps explain why she would high-tail it down the Katy freeway service road to get away from the cops. But that terror also applies to a lot of people in Harris County who had traumatic experiences with the police stemming from use of excessive force or even deadly interactions with a parent—most of them Black, impoverished, and decidedly not connected to Crime Stoppers or its board members.

The important point is that there are thousands of criminal charges filed every month and almost no one gets a personal audience with the District Attorney herself. As Mr. Newman, the defense lawyer, told Houston Watch— “many prosecutors don’t have access to Kim Ogg. Let alone random citizens.” Kim Ogg doesn’t get multiple personal pleas in cases where the person fleeing a police officer is the child of a man that officers had killed; and, if she did, without the name of her powerful backers attached to multiple emails while the case is pending resolution—would she even care?

But Rania Mankarious, the CEO of Crime Stoppers, does have direct access to the D.A. So she decided to use her non-profit work email to ask Kim Ogg to do a favor for another Crime Stoppers board member, Jonathan Zadok. And Zadok himself participated in gathering and funneling information to Mankarious with the clear expectation that it would be delivered to the D.A..

Mankarious’s request for special treatment comes amidst a still unfolding scandal around Crime Stoppers and the politicalization of the storied victim’s advocacy organization’s shifting prioritization of resources under her leadership.

Crime Stoppers of Houston used to focus on gathering tips that help solve crimes and compensating the tipsters to keep the information pipeline flowing. Last year, however, the Crime Stoppers tip line both generated 25% fewer solved cases and spent fewer dollars compensating tipsters than it did the year before. And, before Mankarious’s tenure, the organization solved as many as 2.5 times more cases.

Instead of focusing on solving crimes, the New York Times recently reported that the organization sent representatives to testify on behalf of criminal justice bills in the legislature, “asked people to sign an online letter that cast Houston as a dangerous place where criminals no longer feared the law,” and orchestrated a media series in partnership with Fox News—Breaking Bond—that closely resembled campaign-style attack videos against judges up for re-election this year. As one legal ethics professor told the New York Times, the organization’s “election-focused appearances came closer to that line than most nonprofits are willing to go” and “would give me some heartburn.”

That campaigning aligns perfectly with the political and policy priorities of D.A. Ogg, who has publicly chastised and threatened the same groups of judges, called for public pressure campaigns against them, and allegedly recruited prosecutors from her office to run against a handful of them this election cycle. This alignment of vision between Crime Stoppers and Ogg is particularly fraught because, as the Houston Chronicle recently reported, last year Ogg “donated $500,000 to the non-profit—which has a room in its headquarters named for the DA’s Office.” This dynamic creates the appearance that Ogg is paying for the non-profit’s efforts to whip up media sensationalism that serves her political and policy goals.

This broader context, coupled with the fact that Ms. Mankarious sent the email from her non-profit work email, transforms what otherwise would scan as an improper request from a friend into the appearance of something far more nefarious: a scenario where a needed and trusted business partner is requesting a favor in the course of an ongoing and reciprocal pattern of dealings.